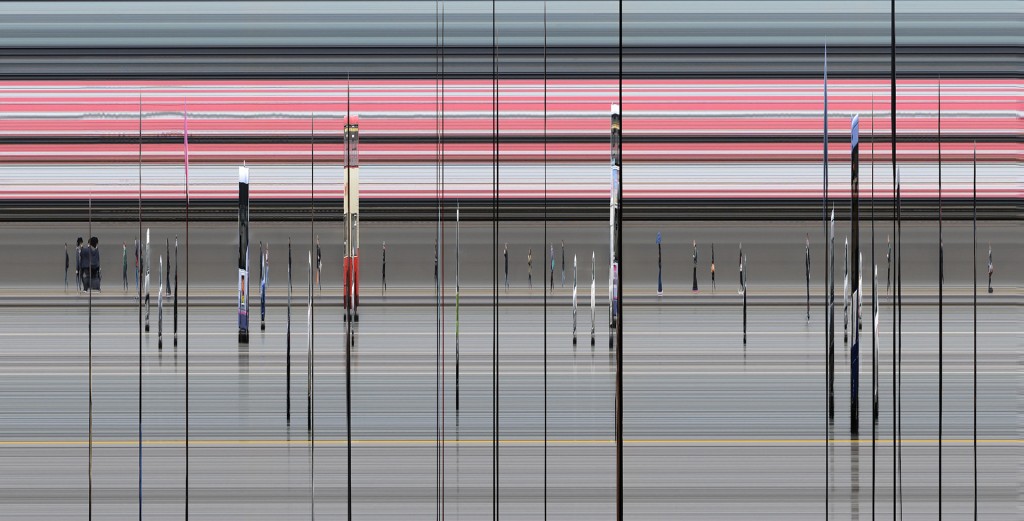

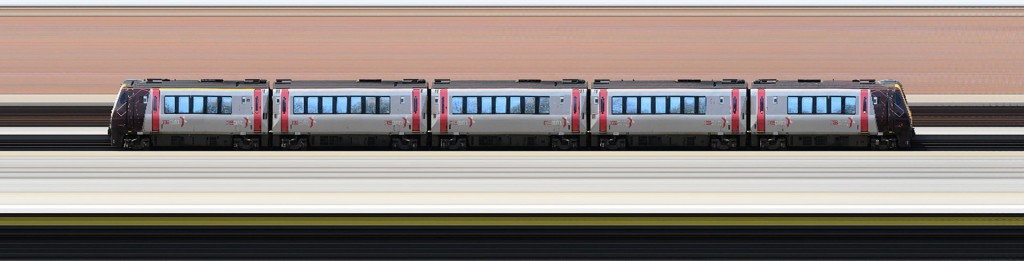

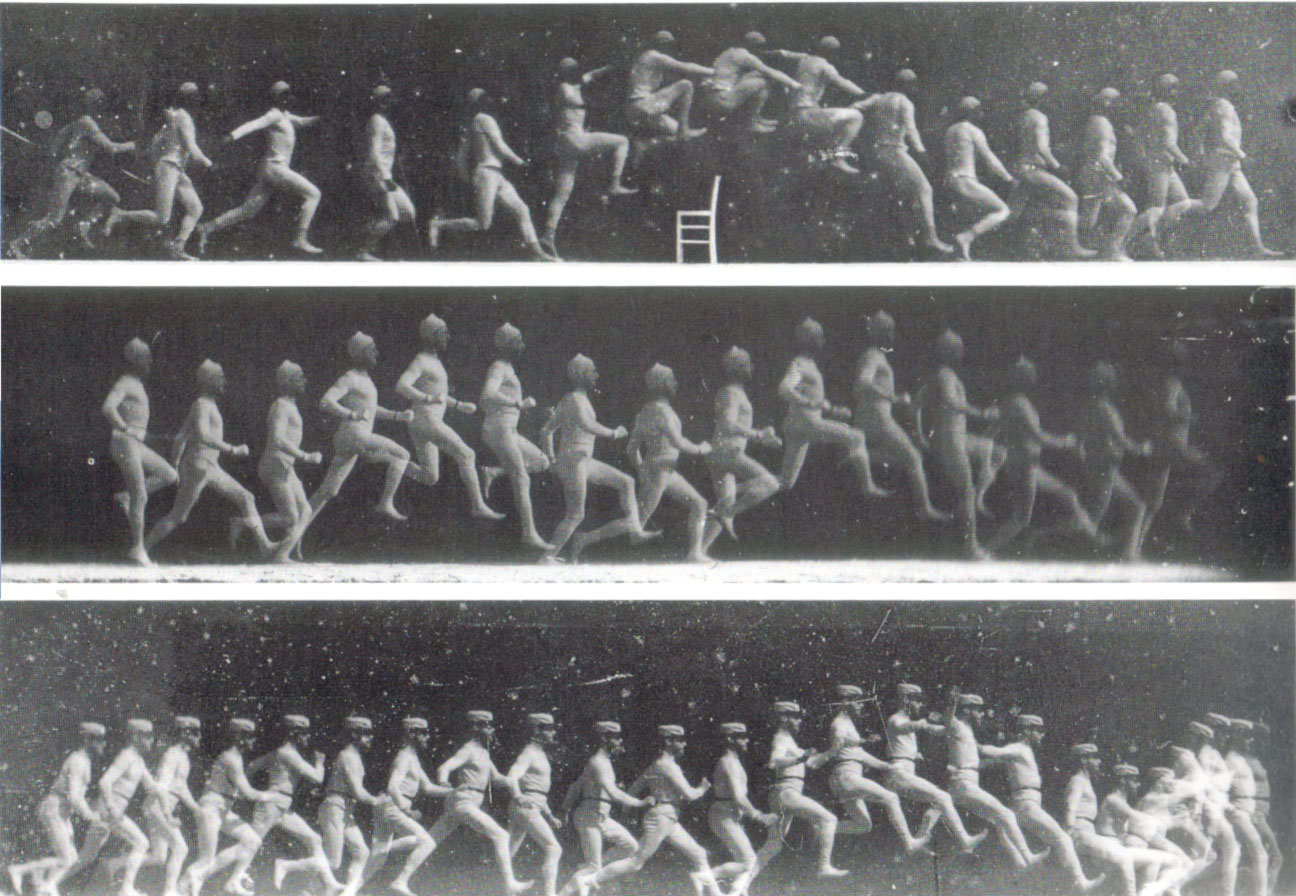

Here is some of the code that I had to use to process the videos into stills, scan them, and then convert them back into video again. I think that the code itself has a part in my work, and I am considering it being part of the work itself, showing directly how technology interacts with the world in which we live, or at very least that algorithms can be a functioning part of an art piece.

import java.applet.*;

import java.awt.Dimension;

import java.awt.Frame;

import java.awt.event.MouseEvent;

import java.awt.event.KeyEvent;

import java.awt.event.FocusEvent;

import java.awt.Image;

import java.io.*;

import java.net.*;

import java.text.*;

import java.util.*;

import java.util.zip.*;

import java.util.regex.*;

void setup() {

size(1280, 720);

setupControlP5();

textFont(createFont("Arial", 18));

smooth();

}

void draw() {

background(0xffE0E4CC);

if (background == null) {

displayExplanation();

} else {

background.update();

}

displayControls();

}

abstract class Processing {

// ============= GENERAL VARIABLES ============= //

ArrayList outputBuffer = new ArrayList ();

int inputWidth, inputHeight, inputFrames, outputFrames, inputFrame;

int batchSize, totalBatchCount, batchCount, saveCount;

int readFirstFrame, readLastFrame, framesToRead;

int maxMemory, totalMemory, freeMemory;

String[] loadFilenames;

PImage currentImage;

String outputName, outputDir;

boolean done;

int displayX, displayY, displayHeight, displayWidth;

float barWidth, barHeight;

int startTime;

// ============= SPECIAL VARIABLES ============= //

int memReserved = 100;

String fullPath, outputFormat;

boolean reverseOrder, invertEffect;

char direction;

// ============= CONSTRUCTOR ============= //

Slitscanner() {

fullPath = currentInputDirectory;

outputFormat = currentOutputFormat;

reverseOrder = toggleReverseOrder.getState();

if (currentTab == 0) {

if (currentDirection == 0) { direction = 'x'; } else { direction = 'y'; }

} else {

if (currentDirection <= 1) { direction = 'x'; } else { direction = 'y'; }

if (currentDirection == 1 || currentDirection == 2) { invertEffect = true; }

}

setupSlitscanner();

}

// ============= SUBTYPE FUNCTIONS ============= //

abstract void createBuffer();

abstract void determineOutput();

abstract void processFrame();

abstract void nextBatch();

// ============= SETUP FUNCTIONS ============= //

void setupSlitscanner() {

loadFilenames();

if (loadFilenames.length > 0) {

determineInput();

createBuffer();

determineOutput();

createOutputName();

createOutputDir();

setTextareaInfo();

setDisplaySettings();

setStartSettings();

}

}

void loadFilenames() {

java.io.File folder = new java.io.File(fullPath);

java.io.FilenameFilter imgFilter = new java.io.FilenameFilter() {

public boolean accept(File dir, String name) {

String lowcase = name.toLowerCase();

return lowcase.endsWith(".jpg")

|| lowcase.endsWith(".jpeg")

|| lowcase.endsWith(".png")

|| lowcase.endsWith(".tga");

}

};

loadFilenames = folder.list(imgFilter);

if (reverseOrder) { Arrays.sort(loadFilenames, Collections.reverseOrder()); }

}

void determineInput() {

PImage tempImage = loadImageFast(fullPath + "/" + loadFilenames[0]);

inputWidth = tempImage.width;

inputHeight = tempImage.height;

inputFrames = loadFilenames.length;

}

void createBufferWHM(int w, int h, int maxBuffer) {

PImage tempImage;

if (currentTab == 1 && firstImage.getState()) {

tempImage = loadImageFast(fullPath + "/" + loadFilenames[0]);

} else {

tempImage = createImage(w, h, RGB);

}

maxMemory = int(Runtime.getRuntime().maxMemory()/1000000);

for (int i=0; i 0) {

int elapsedTime = millis() - startTime;

int hours = elapsedTime / (1000*60*60);

int minutes = (elapsedTime % (1000*60*60)) / (1000*60);

int seconds = ((elapsedTime % (1000*60*60)) % (1000*60)) / 1000;

completed = "Rendering completed in " + hours + " hours " + minutes + " minutes and " + seconds + " seconds!";

buttonRender.setLabel("Click here to start rendering");

textAreaInfo.setText("\n This text area will display information about:\n input, output, memory & batchCount");

} else {

completed = "No image files (jpg, png, tga) in specified directory!";

}

slitsP5 = null;

System.gc();

}

PImage loadImageFast(String inFile) {

if (inFile.toLowerCase().endsWith(".jpg") || inFile.toLowerCase().endsWith(".jpeg") || inFile.toLowerCase().endsWith(".png")) {

byte[] bytes = loadBytes(inFile);

if (bytes != null) {

Image image = java.awt.Toolkit.getDefaultToolkitlol().createImage(bytes);

int [] data= new int [1];

PImage pi = null;

try {

java.awt.image.PixelGrabber grabber = new java.awt.image.PixelGrabber(image, 0, 0, -1, -1, false);

if (grabber.grablolPixels()) {

int w = grabber.getWidth();

int h = grabber.getHeight();

pi = createImage(w, h, RGB);

arraycopy(grabber.getPixels(), pi.pixels);

}

}

catch (InterruptedException e) {

System.err.println("Problems! Defaulting to loadImage(). Error: " + e);

return loadImage(inFile);

}

if (pi != null) {

return pi;

}

return loadImage(inFile);

}

return loadImage(inFile);

}

return loadImage(inFile);

}

}

class DimensionalSwap extends Slitscanner {

void createBuffer() {

if (direction == 'x') {

createBufferWHM(inputFrames, inputHeight, inputWidth);

} else if (direction == 'y') {

createBufferWHM(inputWidth, inputFrames, inputHeight);

}

}

void determineOutput() {

batchSize = outputBuffer.size();

framesToRead = readLastFrame = inputFrames;

if (direction == 'x') { outputFrames = inputWidth; }

else if (direction == 'y') { outputFrames = inputHeight; }

totalBatchCount = ceil((float) outputFrames / batchSize);

}

void nextBatch() {

batchCount++;

inputFrame = 0;

}

void processFrame() {

if (direction == 'x') {

int maxX = min(saveCount+batchSize, inputWidth);

for (int x=saveCount; x

I then converted this code into a scrolling screen, emulating a computer console, I could have gone further with the animation, perhaps made it closer to a real console screen, however I just wanted to play with displaying the code as part of the work itself. The video is a minute long (the same time that is optimal to produce the slitscan vehicle videos) and can be looped easily - so that it can be displayed in the exhibtion space if I choose to include it as the artwork itself.

.jpg)

.jpg)